Il fatturato di Alibaba è cresciuto, nel trimestre terminante il 12 agosto, del 28% metre il risultato operativo “solo” del 23%.

Ciò è dovuto ai suoi investimenti sul mobile internet (acquisti e- commerce fatti sugli smartphone) settore che ha segnato un + 225%.

Alibaba ad agosto ha anche acquisito una partecipazione in una catena di negozi specializzati in elettronica, la Suning Electronics , così da poter controllare ancora meglio la catena logistica ed operare direttamente sia da dei drive che da dei magazzini di negozio, come , per esempio hanno sempre fatto Tesco ed Esselunga.

The Economist, infatti sottotitola l’articolo sotto con “Clicks to bricks” (dai click – dei soli personal computer -ai mattoni..)

Alibaba

Clicks to bricks

The Chinese online giant is looking for new sources of growth

First, he must win over investors. The firm’s shares have fallen sharply from their peak of $119 late last year, though at around $74 they remain above the $68 price at which they (or rather, shares in a “variable interest entity” linked to Alibaba, and registered in the Cayman Islands) were floated last September. On August 12th Alibaba unveiled its latest results. Its quarterly revenues grew by 28% year on year to 20.2 billion yuan ($3.3 billion), and profits rose by 23% to 10.6 billion yuan. Yet investors were still disappointed. The firm now plans to spend up to $4 billion on buy-backs to bolster its share price.

Part of the reason that profit growth was not stronger is that Alibaba is investing heavily in such growth areas as the mobile internet. Promisingly, its quarterly revenues from mobile services, of 8 billion yuan, represent a year-on-year leap of 225%. They now make up half of the firm’s total e-commerce revenues from China, up from just 19% a year earlier. With economic growth cooling in China’s big cities, the firm is making a big push to develop e-commerce among rural consumers. China has relatively few bricks-and-mortar shops per head of the population compared with other large economies. Studies show people outside its big cities are ready to spend a higher share of their incomes on online shopping, and Alibaba aims to tap into their desires.

It is also seeking more e-commerce customers beyond China’s borders. Earlier this month it said Michael Evans, a Canadian banker who used to work at Goldman Sachs, would take charge of its international efforts. Macy’s and Costco, two big American retailers, have already agreed deals to use Tmall Global, one of Alibaba’s online platforms, to sell goods to Chinese shoppers with fewer delays and customs hassles than they had previously faced, since they can now use Alibaba’s bonded warehouses in China’s free-trade zones.

The warehouses are one aspect of Alibaba’s evolution from being an “asset-light” firm. China’s woefully inefficient logistics network, which acts as a brake on e-commerce growth, has forced the firm to get its hands dirty. Two years ago it organised Cainiao, a consortium that runs a digital platform linking more than a dozen logistics providers, 1,800 distribution centres and more than 100,000 dispatch points.

Now, Alibaba is investing in bricks and mortar too, to keep pace with rivals. One of its competitors, JD, has taken an “asset-heavy” approach to e-commerce akin to Amazon’s in America. JD has spent a fortune developing warehouses and logistics networks. This month, it announced a 4.3 billion yuan investment in Yonghui Supermarket, a big grocery chain, to boost its “online to offline” (O2O) offering, in which customers choose and pay for goods online but collect them from, or have them delivered by, a shop. Two other Chinese online giants, Tencent and Baidu, have already struck big O2O deals with Dalian Wanda, a big shopping-centre operator.

This week Alibaba followed suit by making a $4.6 billion investment in Suning, one of China’s largest electronics retailers. Suning will open an online storefront on Tmall, selling home appliances and gadgets, product areas in which JD has bested Alibaba.

The deal will not only let shoppers pick up and return their online purchases at Suning’s stores. It also means that Suning’s delivery network, which reaches every corner of China, will join the Cainiao logistics platform, considerably strengthening it. Cainiao now hopes to offer deliveries in as little as two hours. Suning may also suffer less from “showrooming”, in which shoppers examine products in its shops but buy them online from another retailer.

Alibaba is also ploughing ahead with cloud computing. Its business, Aliyun, is China’s largest cloud provider. So far, smaller Chinese firms are making less use of cloud services than counterparts elsewhere. Alibaba is planning a vast expansion of Aliyun, by offering prices that will tempt even the most frugal of small entrepreneurs. Having already invested heavily in cloud services aimed at Chinese firms, it intends to spend another $1 billion taking Aliyun global.

The biggest future prize for Mr Ma could be online finance, though shareholders in Alibaba’s listed entity may not see all the profits. Ant Financial, a related private company controlled by Mr Ma, houses all of the group’s financial initiatives. Alipay revolutionised online payments by using escrow, which helped buyers and sellers overcome distrust. With some 120m daily transactions, Alipay is miles ahead of the rival payment offering from Tencent.

Ant Financial’s online money-market fund, Yu’E Bao, had roughly 600 billion yuan in assets at the end of June. Ant has also made more than 400 billion yuan of microloans. Though the firm requires no guarantee or collateral, it reports a default rate of below 2%. Ant is headed for a public flotation soon, and analysts think it may be worth up to $50 billion.

Since Alibaba has so much data on the online transactions and other activities of consumers, it is often a better judge of their creditworthiness than the banks. Several countries, including Singapore, are using Sesame, Alibaba’s credit-scoring system, for such things as whether to approve visa applications—so too are Chinese dating websites.

Perhaps the most intriguing look into Alibaba’s future involves a deal struck in July with Unilever. The European consumer-products giant saw its sales in China fall by 20% in the last quarter of 2014. Now Alibaba’s online marketing-services outfit, Alimama, will tap into its parent’s vast consumer database to help Unilever do digital marketing, reach rural consumers and bolster cross-border sales.

In all, Alibaba is developing from a shopping platform into a broad-based provider of online services. Its ambitions will require heavy investment. Some ventures may fail. Others may have their wings clipped by Chinese regulators (their suspension of Alibaba’s online-lottery business was one reason for the group’s slow revenue growth in the past quarter). Investors will grumble about the costs involved and the profits deferred. Still, if even some of these big bets pay off, Mr Ma’s trillion-dollar dream just might come true.

From the print edition: Business

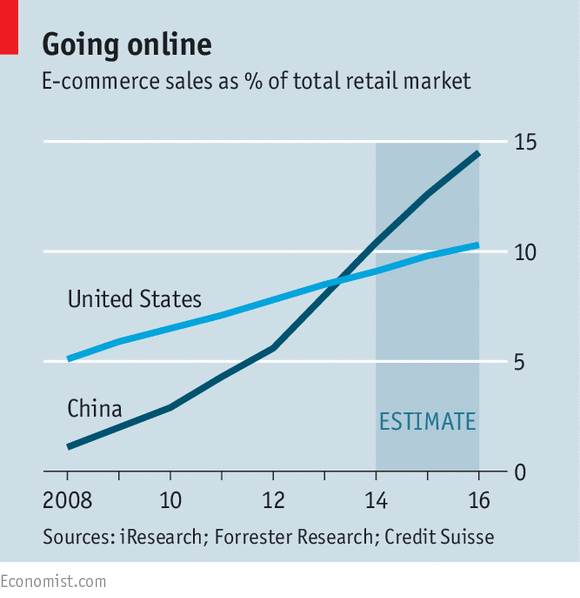

Dal grafico sopra di The Economist sembrerebbe che il fatturato dell’e-commerce in Cina stia superando, quest’anno , quello degli USA ma…

il vero problema di Alibaba, anche se l’azienda , dopo aver conquistato le città, sta puntando alle campagne cinesi e all’estero, sembra essere il rallentamento dei consumi che si è già manifestato nella telefonia:

le vendite di smartphone in Cina sono scese nell’ultimo trimestre, rispetto al trimestre dell’anno passato del 4%

Il mercato cinese è saturo e rappresentando il 30% delle vendite mondiali questo calo ha quindi avuto le conseguenze immediate:

gli smartphones, a livello globale, hanno avuto un incremento “solo” del 13,5%.

Da notare la continua ascesa di Apple e dei produttori cinesi Huawei e Xiaomi rispetto all’ ulteriore calo di quota di mercato di Samsung ( + 2,4%, +1,7% e + 0,6% contro il – 4,3% del gruppo coreano).

In questo contesto la richiesta di prestiti da parte di Alibaba per 2 miliardi di $ ha suscitato qualche perplessità

Il Sole 24 ore del 5 settembre 2015

Sempre ad agosto Walmart ha annunciato che i suoi profitti saranno inferiori a quanto previsto: gli investimenti in risorse umane e internet stanno pesando sui conti, in un contesto americano non facile, soprattutto per il non food (general merchandise)

The Japan News , August 2015

I segnali sono discordanti:

– 4,7% per Asda , filiale di Walmart in Gran Bretagna, dove – dopo tanti anni di controllo dei prezzi – si è scatenata una guerra, acuita dai problemi di Tesco e di Sainsbury’s, che hanno cercato di colmare il divario dei loro prezzi a scaffale nei confronti dei discount Lidl e Aldi che sembrano essere, per il momento, i vincitori della partita rispetto ai supermercati.

Aldi and Lidl’s price war is killing off Britain’s milk industry

German grocers Aldi and Lidl are causing a long and painful price war amongst Britain’s biggest supermarkets.

The battle gives consumers staple and high-end food products at significantly lower prices. Supermarkets, such as Asda and Morrisons, are trying to reclaim market share and bring back shoppers by slashing prices to keep up.

However, the price war is not just hurting incumbent supermarkets’ bottom lines, it’s also starting to destroy Britain’s milk industry.

The National Farmers Union (NFU) is meeting Morrisons today, as part of its round of talks with individual supermarkets, because it says that some grocers are now paying so little for milk that farmers are not able to cover their costs. If the price war continues, farmers will not be able to make ends meet.

The NFU said it costs farmers 62 pence to produce 2.4 litres (4 pints) of milk. However, at the lowest price, some farmers are paid just 48 pence for the same amount of milk. This means that farmers actually lose money by producing and selling milk. On average, British supermarkets sell a bottle of milk at this size for 94 pence.

British dairy organisation AHDB Dairy also confirmed that milk prices per litre fell by over a quarter over the last 12 months. The price per litre fell to 24.06 pence in May. However, farmers say it costs around 30-32 pence to produce one litre of milk.

Aldi, Lidl, Morrisons, and Asda were all targeted by campaign farming campaign groups because they are the supermarkets that give some of the lowest prices.

Morrisons have since said it will not lower milk prices any more. Aldi also contacted Business Insider to make it clear that the group does not buy directly from farmers and that the price it pays “has remained consistently above the farm gate price.”

Researchers at Kantar Worldpanel confirmed that offering low prices for grocery, and in turn sparking a price war, is helping some of these supermarkets to significantly grow.

“Competition is increasingly intense within the grocery market with price reductions and money-off vouchers becoming the norm,” said David Berry, director at Kantar Worldpanel, this month.

“The strongest performer has been Lidl, with impressive sales growth lifting its share of the market to an all-time high of 9.0%.

The discounter has recruited a record number of customers this quarter, with 66% of all Irish householders visiting Lidl at least once during this time.”

Supermarkets, such as Sainsbury’s, have all revealed that they are suffering amid the intense price war.

“Trading conditions are still being impacted by strong levels of food deflation and a highly competitive pricing backdrop,” said Sainsbury’s CEO Mike Coupe last month. “These pressures, including the effect of our own targeted price investment, have led to a fall in like-for-like sales for the quarter.

Sainsbury’s reported a 2.1% drop in like-for-like sales, excluding fuel, for the 12 weeks to June 6, in July.

In June, Sainsbury’s cut the price of one and two pints of milk in order to match Aldi and Lidl’s.

Update – Aldi provided Business Insider with the following statement:

“We purchase milk from three processors in the UK and do not buy directly from farmers. The price we pay from milk has remained consistently above the farm gate price and we have not reduced the amount we pay our processors.

“It is important to note that the retail price for our milk is not linked in any way to the price we pay processors. Any reduction in the retail price is absorbed by Aldi and is not passed on to our processors.

“As part of our commitment to the UK’s dairy industry, we only source milk from Red Tractor assured farms. All of our cream and butter products are produced using British milk and we are signatories of the NFU’s ‘Backing British Farming’ charter.”

Read more: http://uk.businessinsider.com/aldi-and-lidls-low-milk-prices-hurts-uk-farming-2015-8#ixzz3l2fCcAy3

+ 7,3%, a superficie paragonabile, per i Neighborhood Markets (letteralmente negozi di vicinato, molto più piccoli dei normali Supercenter di Walmart).

Walmart pensa di aprirne 170 quest’anno: essi si andranno ad aggiungere ai 350 già esistenti

prima stesura del 1° di settembre 2015

Condividi questo articolo sui Social Network: