Le birre artigianali dlle Maltus Faber di Genova

Prima stesura: 7 settembre 2015, ultimo aggiornamento del 21 settembre 2015

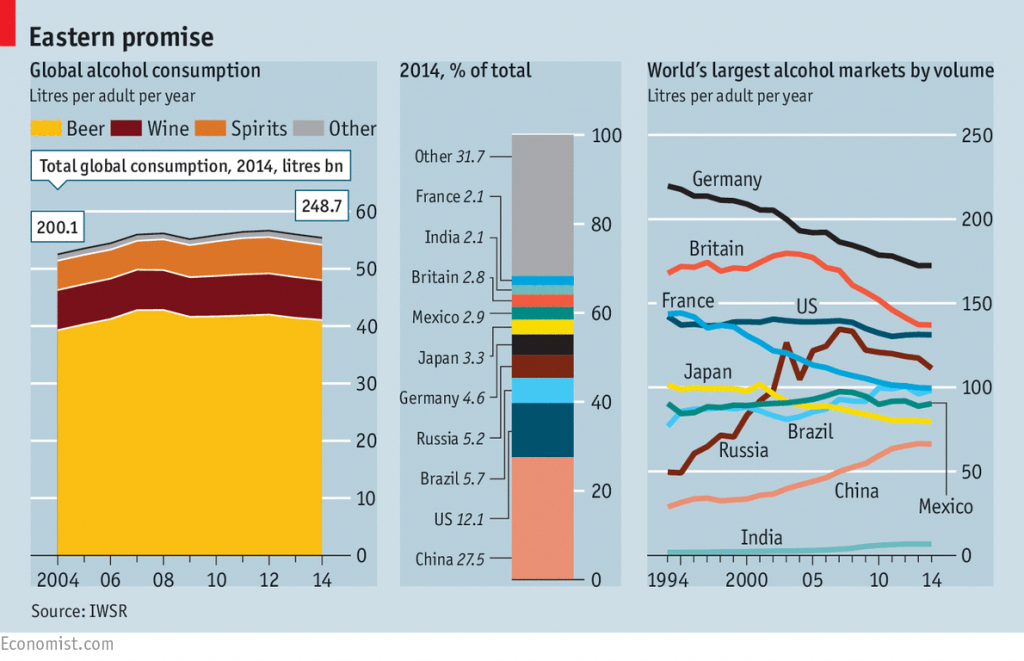

Il mercato dell’alcool sta rallentando sempre di più come avevamo evidenziato in Come si evolvono i consumi di alcool.

A luglio The Economist ha segnalato che il calo dei consumi pro capita nei paesi evoluti nel 2014 non è stato recuperato dai paesi emergenti

Si è passati da 56,6 litri nel 2012 a 55,4 litri nel 2014 (- 2,1%) e una crescita globale in ettolitri pari praticamente a zero.

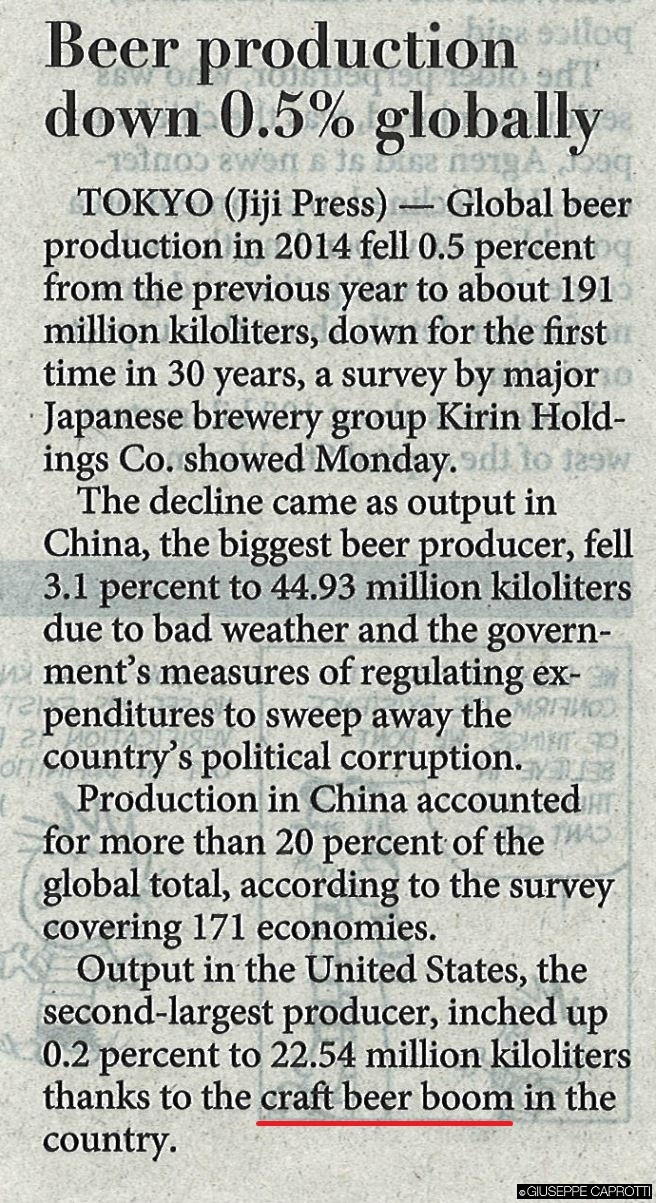

Il calo dei consumi della birra nel mercato cinese sta già avendo effetti negativi sulle vendite mondiali.

Lo ha registrato un’inchiesta della giapponese Kirin

La Cina, nel 2014, ha rappresentato all’incirca il 20% del mercato globale della birra (il dato combacia con quello della ristorazione, dove la Cina pesa quasi il 20%) e il suo calo del 3,1% si è fatto sentire:

era da 30 anni che i consumi di birra non decrementavano

The Japan News , 12 agosto 2015

Va doverosamente segnalato però che, a fronte di un – 0,5% di decremento a livello globale, il mercato statunitense è salito leggermente (+ 0,2%) grazie al boom della birra artigianale (+ 18%, vedi The Economist, sotto).

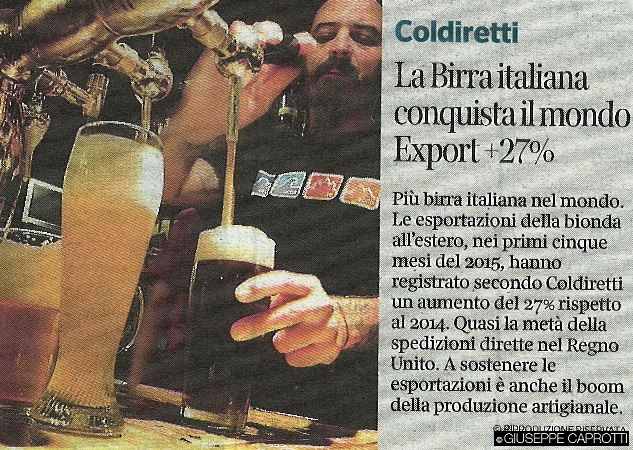

Questo comparto sta dando grandi soddisfazioni anche ai produttori italiani come segnala Coldiretti

Corriere della Sera agosto 2015

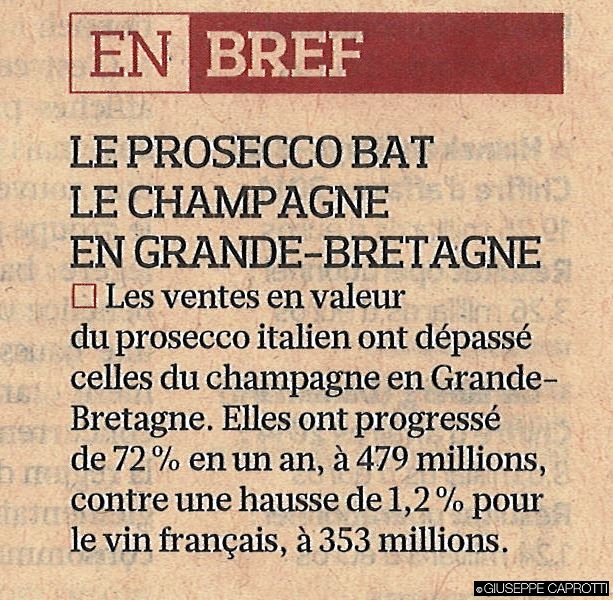

ma non è l’unica eccezione: il prosecco si comporta benissimo e straccia ogni record:

le Figaro fa un’amaro confronto tra un + 72% per il Prosecco, con 479 milioni di euro e il + 1,2% per il vino francese, per 353 milioni di euro, in Gran Bretagna

Le Figaro de 20 agosto 2015

L’ evoluzione del mercato delle bevande alcoliche dipende molto dai prodotti fatti in casa.

Essi sono di uso comune in paesi con consumi statici o in decremento (es. quelli della “vodka belt”: Russia, Ucraina, Polonia, etc.) ma anche in paesi ad alto potenziale in Africa o come l’India, dove – per esempio, a causa dell’alta tassazione (150%) dei prodotti importati- si tendeva fino ad adesso a consumare whisky fatto in casa, con i rischi e pericoli connessi a questo tipo di fabbricazione.

Non a caso, in India, Diageo, nel 2014, ha comprato la maggioranza del produttore locale di whisky United Spirits Limited.

Da segnalare anche :

1) l’eccezione delle foires aux vins, con La GD e le promozioni dei vini in Francia, dove Lidl mette a segno un + 20%

2) la crescita delle birre analcoliche nei paesi mussulmani: non solo gli alimenti halal raddoppieranno entro il 2019 ma, secondo Euromonitor, nel 2030 i consumatori mussulmani peseranno il 26% dei consumi mondiali

fonte: Il Sole 24 ore del 14 settembre 2015

3) la crescita del vino biologico:

i consumatori , in Italia, sono passati dal 2% del 2013 al 16,8% del 2015 e le vendite, nella GD, nel primo semestre 2015, sono raddoppiate

“Piccolo è bello”, come avevamo già evidenziato in USA : le nuove tendenze del cibo.

le vendite di birra in Nigeria e Mozambico, tra aprile e giugno 2015- fonte Le Monde del 18 settembre – sono salite del 25%.

L’Africa, con il Sud America (Perù e Colombia in particolare) sono uno degli obiettivi del tentativo di fusione tra ABInBEV (marchi: Budweiser, Corona, Leffe, Beck’s, Stella Artois)

e SABMiller (marchi: Peroni, Pilsener Urquell, Foster’s, Miller) che si potrebbe concretizzare il 14 ottobre

A giant drinks merger

Beer monster

AB Inbev may combine with SABMiller, in a flat market for big beer brands

THE history of the world’s biggest brewer is one of unquenchable thirst. In 1989 Jorge Paulo Lemann and two partners bought a middling Brazilian beer company named Brahma for $50m. A decade later Brahma acquired Antarctica, a rival, to become AmBev. In 2004 a merger with Interbrew, the Belgian seller of Stella Artois and Beck’s, created InBev. Four years later, InBev paid $52 billion for Anheuser-Busch of the United States. As if those deals weren’t dizzying enough, in 2012 the new Anheuser-Busch InBev paid $20 billion for full control of Grupo Modelo of Mexico.

Now may come its boldest deal yet. On September 16th SABMiller, the world’s second-biggest brewer, confirmed that it is being courted by AB InBev. The combined firm would earn roughly half the industry’s profits and sell one in every three pints of beer quaffed worldwide.

The announcement comes at a sobering time for big brewers—in June McKinsey, a consulting firm, said the industry faced “its greatest challenge in 50 years”. Consumption in many big markets has been as flat as cask ale. In America the buzz belongs to “craft” brewers, whose volumes jumped by 18% last year even as total beer sales stayed level. Some markets have fared worse. In Germany, where beer is a point of national pride, consumption per person has plunged by one-third since the 1970s.

Little wonder, then, that big brewers and investors have mulled various tie-ups. Last year SABMiller tried and failed to buy Heineken, the third-biggest beer company. June brought rumours that Mr Lemann’s private-equity vehicle, 3G, would buy Diageo, the world’s biggest distiller, perhaps to combine it with AB InBev. More recently, analysts have weighed a merger of Diageo and SABMiller.

Some of these combinations would have merit. But there is a logic for AB InBev to make this particular bid at this particular moment. It is losing its fizz in its two main markets. In Brazil a weak economy is hurting sales. In America its share of volumes was an impressive 45% in 2014, but that is five percentage points below what it was in 2009, according to Euromonitor, a market-research firm. So, buying SABMiller looks attractive, for at least three reasons.

First, AB InBev has already snapped up other big, appealing targets, explains Trevor Stirling of Sanford C. Bernstein, a research firm. In the past, it has sliced the costs of newly acquired assets, as is 3G’s way. In the three years after AB InBev bought Anheuser-Busch, its American profit margin rose by 13 percentage points. AB InBev plans to boost Grupo Modelo’s profit margin by 18 percentage points over the same period. SABMiller is already pretty lean, but a merger would offer some scope to widen its margins.

Second, the merger would help AB Inbev extend its global reach. SABMiller earns almost a third of its profits in Africa, where AB InBev’s sales are negligible. A combination would also help AB InBev serve more drinkers in Colombia and Peru.

Third, SABMiller looks cheap. Its share price has slumped in the past year, thanks to a weak South African rand and Colombian peso. Slower growth in emerging markets, where SABMiller earns 72% of its profits, has not helped. If emerging economies resume their brisk climb, investing in SABMiller could pay off handsomely.

Under the takeover rules in Britain, where SABMiller is listed, AB Inbev must make a formal offer by October 14th. SABMiller’s board is likely to reject its initial approach, and may seek another deal to avoid being taken over. However, its attempts to join up with Heineken got nowhere. It is not obvious that there are other good targets. “If that deal was out there,” argues Mr Stirling, “they would have done it already.” SABMiller’s two biggest shareholders are Altria, a tobacco giant, and the Santo Domingo family of Colombia. If AB InBev’s terms are sweet enough, they will probably support a merger.

Antitrust regulators are another big barrier, though AB InBev could work to appease them. For example, it could sell SABMiller’s stake in MillerCoors, in America, and in CR Snow, China’s biggest brewer. It has already done something similar. After it bought Grupo Modelo, AB InBev calmed American regulators by agreeing to sell the Mexican firm’s American beer business for $4.75 billion. Shedding a business or two can be justified, after all, in the name of acquiring a much bigger one.

From the print edition: Business

Lo scaffale di Peroni (SABMiller) da Eataly Smeraldo, a Milano

Condividi questo articolo sui Social Network: